When you take a medication like warfarin, phenytoin, or digoxin, even a tiny change in your blood level can mean the difference between treatment working and something going seriously wrong. These are NTI drugs - narrow therapeutic index drugs - and they’re not like most other medicines. The FDA treats them differently because the margin for error is razor-thin. For generic versions of these drugs, the rules for proving they work the same as the brand-name version are far stricter than for regular medications. If you’re a patient, pharmacist, or healthcare provider, understanding these standards isn’t just technical - it’s critical for safety.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

An NTI drug is one where small changes in dose or blood concentration can cause serious harm. The FDA defines these drugs using a clear metric: a therapeutic index of 3 or less. That means the lowest dose that causes toxicity is no more than three times the lowest dose that works. For example, digoxin - used for heart rhythm problems - has a therapeutic index of about 2. If your blood level goes just a bit too high, you risk dangerous heart arrhythmias. Too low, and the drug doesn’t work. There’s no room for guesswork.

The FDA didn’t always have this exact number. Before 2022, the definition was based on expert opinion and clinical experience. But after analyzing over a dozen drugs, researchers found that 10 out of 13 NTI drugs had a therapeutic index of 3 or lower. That’s when the agency settled on ≤3 as the official cutoff. It’s not perfect, but it’s measurable, consistent, and backed by data.

Common NTI drugs include:

- Carbamazepine (for seizures)

- Phenytoin (epilepsy)

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Digoxin (heart failure)

- Valproic acid (mood stabilizer)

- Tacrolimus and cyclosporine (organ transplant immunosuppressants)

- Lithium (bipolar disorder)

Notice something? These aren’t everyday meds like ibuprofen or metformin. They’re high-stakes drugs used in complex, life-threatening conditions. That’s why the FDA treats them differently.

How Bioequivalence Works for Regular Drugs

For most generic drugs, the FDA requires proof of bioequivalence - meaning the generic delivers the same amount of drug into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name version. The standard test? The 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand drug must fall between 80% and 125%. That’s a 45% range. It sounds wide, but for most drugs, it’s safe. A 20% difference in exposure? Usually no big deal.

Take a generic version of a blood pressure pill. Even if your body absorbs 15% less of the active ingredient, your blood pressure still stays controlled. The body can handle that variation. But with NTI drugs, 15% less - or 15% more - can be dangerous. That’s why the old standard doesn’t work here.

The FDA’s Stricter Rules for NTI Drugs

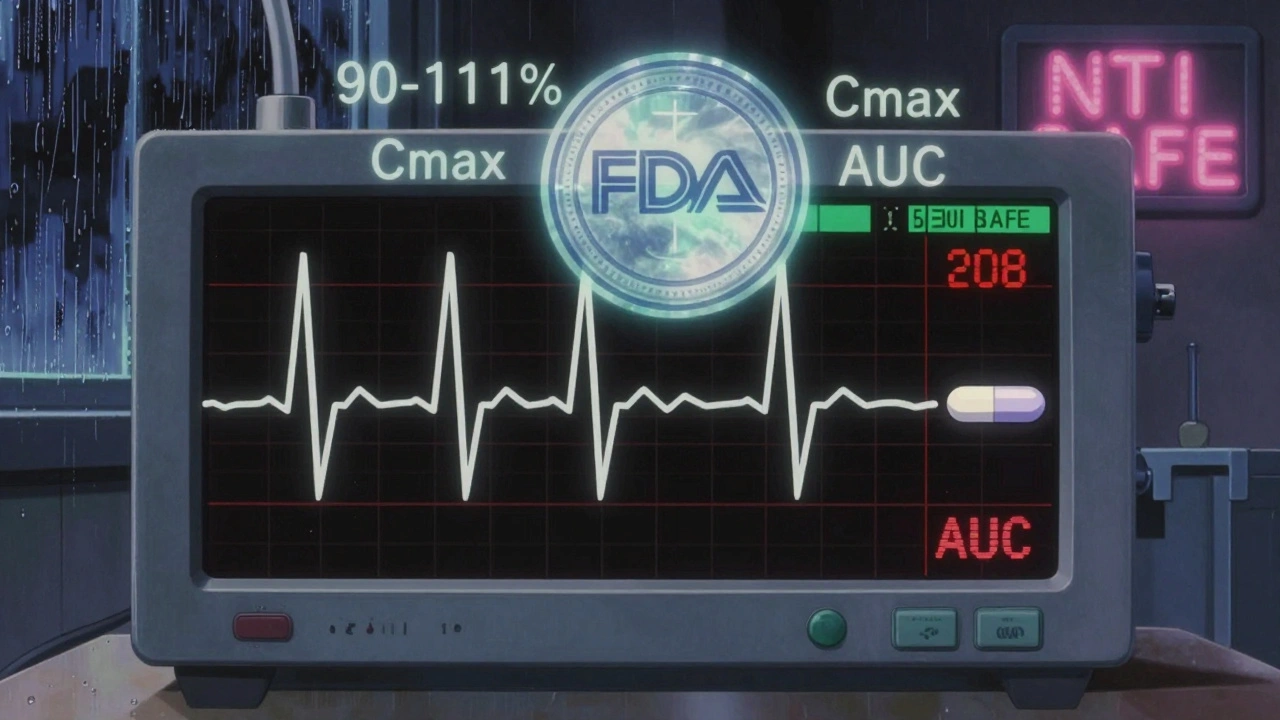

In 2010, the FDA’s advisory committee voted 11-2 that the standard 80-125% range was too loose for NTI drugs. They recommended a tighter window: 90% to 111%. That’s a 21% range - more than half as wide as the standard. Since then, the FDA has built a detailed framework around this.

Here’s how it works in practice:

- 90-111% bioequivalence range: The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic to brand drug must stay within this tighter range. This applies to both peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC).

- Reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE): For NTI drugs with moderate variability (within-subject variability > 0.21), the FDA allows scaling. But even then, the generic must still meet the 80-125% limit as a backup. It’s a double-check system.

- Within-subject variability limit: The upper 95% confidence limit for the ratio of within-subject variability between the generic and brand drug must be ≤ 2.5. This ensures the generic doesn’t vary more than the brand from person to person or day to day.

- Quality control tighter too: The FDA requires generic NTI drugs to meet a 95-105% assay range - meaning the actual amount of active ingredient must be extremely close to the label claim. For non-NTI drugs, it’s 90-110%.

These aren’t just guidelines - they’re mandatory. If a generic doesn’t meet all these criteria, it won’t get approved.

Why This Matters for Patients

Let’s say you’re on warfarin. Your doctor has you at exactly 2.5 mg daily. Your INR is stable. You switch to a generic version that meets the 90-111% standard. That’s good - the FDA says it’s safe.

But here’s the catch: not all generics are the same. Studies have shown that two different generic versions of the same NTI drug - both approved by the FDA - can still behave differently from each other. One might have a geometric mean ratio of 1.05, another 1.09. Both are within the 90-111% range. But if you switch between them, your blood level could shift enough to affect your INR.

This is why some hospitals and clinics don’t automatically switch patients between generic NTI drugs. Even if each is FDA-approved, the cumulative effect of multiple switches can be unpredictable. That’s not a failure of the system - it’s a reminder that NTI drugs demand extra caution.

The FDA acknowledges this. They say real-world data shows generic NTI drugs are safe and effective overall. But they also admit that confusion exists - especially among pharmacists and patients. That’s why they’re pushing for better education and clearer labeling.

How NTI Rules Compare Globally

The FDA’s approach is unique. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Health Canada mostly just tighten the bioequivalence range to 90-111% and leave it at that. They don’t use the scaled method or the variability comparison. The FDA’s method is more complex, but also more flexible. It accounts for how variable the original drug is - which makes sense if the brand drug itself swings a lot in different people.

But this complexity also means more work for manufacturers. NTI drug studies require replicate designs - meaning patients take the drug multiple times under controlled conditions. That’s expensive and time-consuming. It’s one reason why fewer generic NTI drugs hit the market compared to regular generics.

What’s Not on the Public List

You won’t find a complete public list of NTI drugs on the FDA website. That’s intentional. The agency doesn’t classify drugs in bulk. Instead, they issue product-specific guidance for each drug. So if you’re looking to see whether a generic version of a drug is held to NTI standards, you have to check the guidance document for that specific drug.

For example, if you search for “tacrolimus bioequivalence,” you’ll find a detailed document outlining the exact 90-111% limits, the variability thresholds, and the study design requirements. The same goes for phenytoin, warfarin, and others. This approach gives the FDA flexibility - they can adjust standards based on new data for each drug.

Challenges and Controversies

There’s a big gap between what the FDA says and what some clinicians believe - especially with antiepileptic drugs. Studies show that generic and brand versions of carbamazepine and phenytoin are bioequivalent under FDA standards. But in real life, some patients report seizures returning after switching. Others report side effects.

Is it the drug? Or is it the patient’s anxiety about switching? Or could there be subtle differences in how the body absorbs the drug over time? The science isn’t settled. The FDA stands by its data, but many neurologists still prefer to stick with brand-name drugs for epilepsy patients.

Some states have laws that require patient consent before substituting an NTI generic. Others ban automatic substitution entirely. That’s not because the FDA’s standards are wrong - it’s because the system is still evolving. Patients need to be informed, and pharmacists need training.

What’s Next for NTI Drugs?

The FDA is working on better ways to classify NTI drugs using more objective metrics. They’re also pushing for global alignment. Right now, if a generic NTI drug is approved in the U.S., it might not meet the standards in Europe - or vice versa. That creates confusion for international patients and manufacturers.

Meanwhile, researchers are studying real-world outcomes for patients on generic NTI drugs. Early data from transplant centers shows stable outcomes with generic tacrolimus. Studies on warfarin users show no increase in bleeding or clotting events after switching. But these are still limited.

One thing is clear: NTI drugs will keep getting more attention. About 15% of newly approved generic drugs in 2022 were NTI drugs. That number is growing. As more of these drugs go generic, the pressure to get the standards right will only increase.

Bottom Line

Generic NTI drugs are safe - when they meet the FDA’s strict standards. But those standards aren’t just a formality. They’re a safety net designed to protect patients from tiny, dangerous changes in drug levels. If you’re taking an NTI drug, don’t assume all generics are the same. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist before switching. Ask if the generic you’re being given meets the 90-111% bioequivalence range. And if you notice any changes in how you feel after switching - speak up. Your feedback helps improve the system.

What does NTI stand for in drugs?

NTI stands for Narrow Therapeutic Index. It means the drug has a very small range between the dose that works and the dose that causes harm. Even small changes in blood levels can lead to treatment failure or serious side effects.

Why are NTI drugs treated differently by the FDA?

Because the margin for error is so small. A 20% difference in blood concentration that’s safe for most drugs can be dangerous for NTI drugs. The FDA uses tighter bioequivalence limits (90-111%) and stricter quality controls to ensure generics are as safe and effective as the brand-name version.

Are all generic NTI drugs the same?

No. Even if two generic versions of the same NTI drug are both FDA-approved, they can behave slightly differently in the body. Studies have shown that some generics approved under NTI standards aren’t bioequivalent to each other. That’s why switching between generics isn’t always recommended without medical supervision.

How does the FDA test bioequivalence for NTI drugs?

The FDA uses replicate studies where participants take the drug multiple times. They measure peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC). The 90% confidence interval must fall within 90-111%. They also check that the variability of the generic drug isn’t higher than the brand’s, using a limit of ≤2.5 for the upper confidence bound.

Can I switch from brand to generic NTI drugs safely?

Yes - if the generic meets the FDA’s strict NTI bioequivalence standards. But because even small changes can matter, it’s best to switch only under your doctor’s guidance and with close monitoring. Don’t switch back and forth between different generics without checking with your provider.

What are examples of NTI drugs?

Common NTI drugs include warfarin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, digoxin, valproic acid, lithium, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine. These are used for conditions like epilepsy, heart failure, organ transplants, and bipolar disorder, where precise dosing is critical.

Ariel Nichole

December 11, 2025 AT 23:25This is such a clear breakdown of NTI drugs - I’ve been a pharmacist for 12 years and even I didn’t realize how much tighter the standards are. The 90-111% range makes total sense when you think about warfarin or digoxin. One tiny swing and someone ends up in the ER. Good job explaining it without jargon.

matthew dendle

December 13, 2025 AT 05:16so the fda says its safe but then says dont switch generics?? sounds like they made a rule so they can say they did something while still letting pharma companies make bank on brand name stuff. classic.

Jean Claude de La Ronde

December 15, 2025 AT 04:57It’s funny how we treat drugs like they’re math equations when they’re really biological chaos. You can measure Cmax and AUC all day, but the human body isn’t a lab rat in a controlled environment. One guy’s gut microbiome might metabolize tacrolimus like it’s candy, another’s might ignore it entirely. The FDA’s standards are elegant… but elegance doesn’t always save lives.

Mia Kingsley

December 16, 2025 AT 01:59Oh please. You think the FDA knows what they’re doing? My cousin switched from brand to generic phenytoin and had a seizure in the shower. They told her it was "within limits." Limits?? My cousin’s brain isn’t a spreadsheet. And now she’s on disability because the system didn’t care enough to get it right.

Aman deep

December 17, 2025 AT 19:44As someone from India where generics are the only option for most people, I want to say thank you for this. We don’t have the luxury of brand-name drugs here, and this info helps me explain to patients why we can’t just swap pills like candy. Even if the numbers look good, we watch closely - INR, levels, how they feel. Science helps, but human care still leads. Keep sharing this kind of stuff - it matters.

Sylvia Frenzel

December 18, 2025 AT 23:23Why are we even talking about this? The US spends billions on healthcare and we can’t even guarantee consistent drug quality? This isn’t innovation - it’s failure. Other countries manage just fine. We’re overcomplicating it because we’re too lazy to fix the real problem: corporate greed.

Aileen Ferris

December 20, 2025 AT 01:35lol so the fda says its safe but then says dont switch between generics?? so like… which one do i pick then? the one that costs less? the one my pharmacy stocks? or the one that makes my head stop spinning??

Sarah Clifford

December 21, 2025 AT 19:15so basically the fda says its fine but then says dont switch?? what even is this?? i’m confused now and my head hurts

Regan Mears

December 22, 2025 AT 23:47Thank you for highlighting the variability issue - this is critical. I’ve seen patients on tacrolimus after transplants switch between two FDA-approved generics and end up with rejection episodes. The numbers say it’s fine, but the body doesn’t read the FDA’s PDFs. We need better tracking systems, not just tighter limits. Maybe even blockchain-based batch tracking? It’s time to move beyond the 1980s-era bioequivalence model.

Ben Greening

December 24, 2025 AT 03:13Interesting that the EMA doesn’t use reference-scaled bioequivalence. Simpler is often better. If the goal is patient safety, maybe we don’t need the complexity - just a tighter, uniform range across the board. Less room for interpretation, fewer regulatory headaches, and more consistency globally.

Vivian Amadi

December 25, 2025 AT 15:59You’re all missing the point. The FDA is a puppet of Big Pharma. They let generics in so they can charge less, but they make the rules so complicated that only the big players can afford to comply. That’s why there are so few generic NTI drugs - it’s not about safety, it’s about monopoly control. Wake up.