Think about the last time you bought something just because everyone else did. Maybe it was a hoodie everyone was wearing, a snack no one had heard of last year, or even the way you talked about your day at school. You didn’t make the choice because it was the best option-you made it because it felt right to fit in. That’s not weakness. That’s social influence-a quiet, powerful force shaping what you like, what you avoid, and what you think is normal.

Why We Copy Without Realizing It

We like to believe we’re independent. That our tastes, habits, and decisions come from deep inside us. But research shows otherwise. In the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch ran a simple experiment: people were shown lines of different lengths and asked to pick which one matched a standard line. Everyone else in the room-actually actors-gave the wrong answer on purpose. Nearly 76% of the real participants went along with the group at least once, even when the answer was obviously wrong. They didn’t lie to be mean. They didn’t misunderstand. They just couldn’t stand being the odd one out. This isn’t just about lines on a page. It’s about how we navigate the world. When your friends start drinking energy drinks, you might start too-even if you don’t like the taste. When your classmates stop wearing hoodies, you ditch yours, even if it’s cozy. We’re wired to align with the group because it feels safer. Our brains treat social acceptance like a reward. Neuroscientists have found that when we agree with our peers, the ventral striatum-a part of the brain linked to pleasure-lights up more than when we make a choice alone. That’s not just psychology. That’s biology.The Two Needs Driving Conformity

Not all peer influence is the same. Two deep human needs drive it: the need to be liked, and the need to belong. Being liked is about approval. You change your opinion because you want someone you admire to think you’re cool. This is strongest when the peer has status-someone popular, confident, or respected. Studies show that when a high-status peer speaks up, others are 38% more likely to follow, even if the opinion is questionable. Belonging is deeper. It’s not about impressing one person. It’s about feeling part of the team. You don’t wear the same shoes because you want praise-you wear them because you don’t want to feel left out. This is why peer groups can shift entire school cultures. If the group starts skipping class, others follow not because they want to, but because staying in feels like standing alone. These aren’t just theories. A 2022 study tracking teens found that 34.7% of conformity came from the need to be liked, and 29.8% came from the need to belong. Together, they explain most of the behavior we label as “peer pressure.”It’s Not Just About Bad Choices

Most people think social influence is dangerous. That it leads to smoking, vaping, or risky behavior. But that’s only half the story. In schools where students see their peers studying hard, volunteering, or speaking up in class, those behaviors spread too. Long-term studies show that teens who conform to academically engaged peers improve their grades by the equivalent of 0.35 standard deviations-enough to move from a C to a B average. In one CDC-backed program, schools trained popular students to model healthy habits like using hand sanitizer or eating lunch in the cafeteria. Within six months, vaping dropped by nearly 19%. The difference? The group’s norm. Influence doesn’t care if the behavior is good or bad. It just follows the crowd. That’s why fixing a problem often means changing who the crowd looks up to-not just preaching against the behavior.

Why Some People Resist-and Others Don’t

Not everyone caves. Some people laugh off peer pressure. Others feel it like a weight. Why? Research shows susceptibility varies widely. Some people have a “susceptibility score” as low as 0.15-meaning they barely budge when others speak up. Others score above 0.85, meaning they’re almost always swayed. This isn’t about personality alone. It’s about brain wiring. fMRI scans show that when someone resists group pressure, their amygdala and prefrontal cortex activate more than usual. That’s the brain’s alarm system and decision center working overtime to say, “This feels wrong.” Age matters too. Adolescents are most vulnerable. Their brains are still learning how to weigh social feedback against personal values. But vulnerability isn’t just about age. It’s about connection. Teens who feel isolated or unsure of their place are 2.3 times more likely to adopt behaviors from peers-even harmful ones-just to fit in. And here’s the twist: sometimes, the people you think are influencing you aren’t even the ones doing it. Studies show we often overestimate how much our close friends shape us. In reality, it’s the less obvious people-the ones you see in the hallway, the ones who post on social media, the ones who just seem to “know what’s cool.” These are the invisible influencers.The Hidden Trap: Thinking Everyone’s Doing It

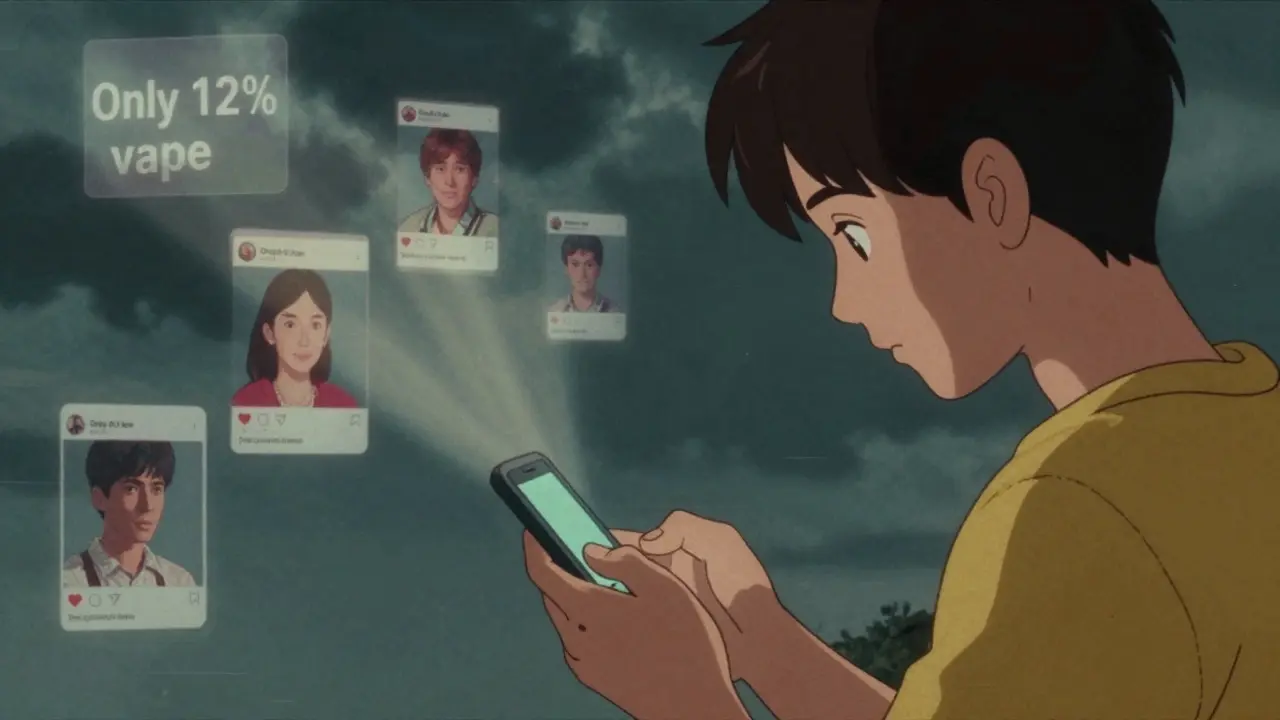

One of the biggest mistakes we make is assuming everyone else is doing what we think they’re doing. In a 2014 study, 67% of high school students believed their peers drank alcohol more often than they actually did. Some thought most kids were vaping daily. The truth? Only 12% were. This gap-called “pluralistic ignorance”-fuels bad behavior. If you think everyone’s doing it, you feel pressured to join. But if you knew the real numbers, you might feel brave enough to stand out. That’s why some of the most effective interventions don’t focus on scaring kids. They focus on correcting the lie. When schools share real data-“Only 1 in 5 students vape”-students change their behavior faster than any lecture ever could. The brain doesn’t respond to fear. It responds to truth.