When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it’s safe and effective? The answer lies in a statistical rule most people have never heard of: the 80-125% rule. This isn’t about how much active ingredient is in the pill-it’s about how your body absorbs it. And it’s the reason millions of generic drugs are approved every year without needing new clinical trials.

What the 80-125% Rule Actually Means

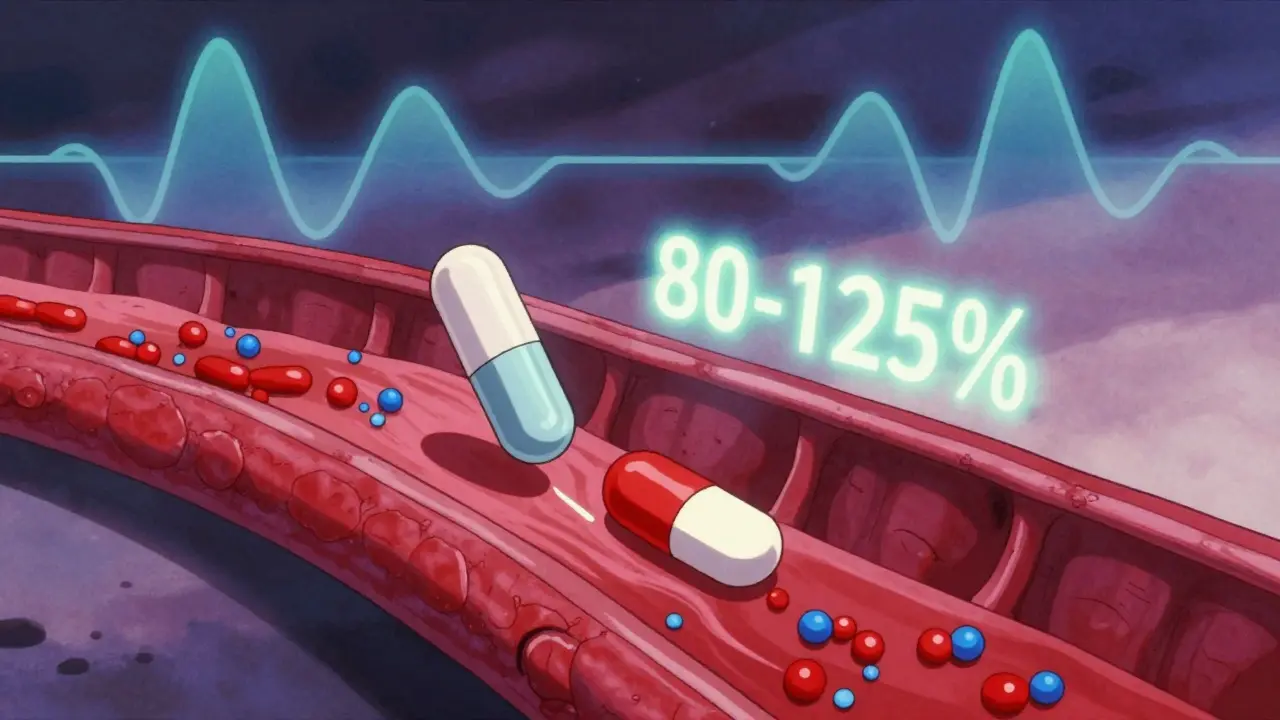

The 80-125% rule is a global standard used by the FDA, EMA, WHO, and other health agencies to decide if a generic drug is bioequivalent to its brand-name counterpart. It doesn’t mean the generic contains 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s a common myth. In reality, most generics contain 95% to 105% of the labeled amount-same as brand drugs.

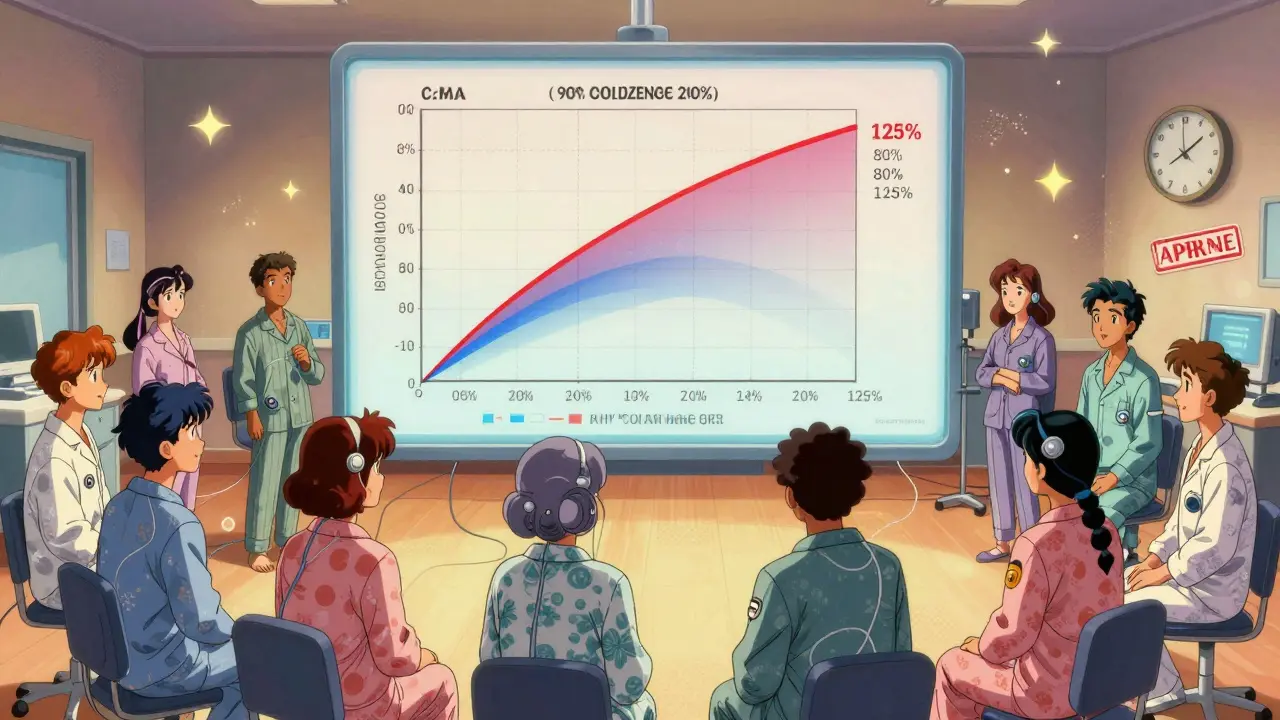

The rule applies to two key measurements taken from clinical studies: AUC (Area Under the Curve), which shows total drug exposure over time, and Cmax, which measures the highest concentration in your bloodstream. These values come from blood samples taken from healthy volunteers after taking the drug.

Here’s the real test: the 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand-name drug’s geometric mean AUC and Cmax must fall entirely between 80% and 125%. If even one point of that interval is outside that range, the drugs aren’t considered bioequivalent-and the generic won’t be approved.

Why Logarithms and Confidence Intervals Matter

Why use a 90% confidence interval instead of the more common 95%? And why do they log-transform the data? It’s not arbitrary.

Drug absorption doesn’t follow a normal bell curve. It follows a log-normal distribution-meaning small differences at low levels matter more than they do at high levels. Taking the logarithm of AUC and Cmax turns multiplicative differences into additive ones. On the log scale, 80% and 125% become symmetrical: -0.2231 and +0.2231. That makes the math work cleanly.

The 90% confidence interval is used because it allows a 5% error on each end. That means there’s a 10% total chance the result could be wrong-enough to catch meaningful differences without being too strict. It’s a balance between safety and practicality. Traditional hypothesis testing wouldn’t work here. If you test two identical drugs with a huge sample size, even a 1% difference could be statistically significant-even if it has zero clinical impact. Confidence intervals fix that by focusing on the range of likely values, not just whether a difference exists.

How It’s Tested in Real Studies

A typical bioequivalence study involves 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. Each person takes both the brand-name drug and the generic, in random order, with a washout period in between. Blood samples are taken over 24 to 72 hours, depending on the drug’s half-life. Researchers then calculate AUC and Cmax for each person and each product.

The data is log-transformed, and the geometric mean ratio is calculated. Then comes the 90% confidence interval. Both AUC and Cmax must pass. If one fails, the whole study fails. There’s no partial credit.

For drugs with high variability-like warfarin or certain epilepsy meds-the standard range can be widened using scaled average bioequivalence (SABE). Under SABE, the range can stretch to as wide as 69.84% to 143.19% if the reference drug itself shows high variability within patients. But that’s the exception, not the rule.

When the Rule Isn’t Enough

The 80-125% rule works well for most oral immediate-release drugs. But it’s not perfect for everything.

Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like levothyroxine, digoxin, and phenytoin have very little room for error. A 10% difference in absorption could mean a seizure or a dangerous overdose. For these, the FDA now recommends tighter limits: 90% to 111%. Some countries have already adopted this.

Complex formulations-like extended-release pills, inhalers, or topical creams-are harder to test with blood levels alone. The FDA’s Complex Generics Initiative is working on new methods, including in vitro dissolution testing and computer modeling, to replace or supplement human studies for these products.

And then there’s the issue of food effects. Some drugs absorb poorly on an empty stomach. For those, studies must be done both fasted and after a meal. If the food effect differs between brand and generic, that’s a red flag-even if both meet the 80-125% rule in the fasted state.

Why This Rule Works Better Than You Think

When the rule was first proposed in the 1980s, some scientists argued it was arbitrary. No clinical trials had proven that a 20% difference in exposure was harmless. But decades of real-world data have backed it up.

A 2020 FDA analysis of over 2,000 generic drugs approved between 2003 and 2016 found that only 0.34% required label changes or recalls due to bioequivalence concerns after hitting the market. That’s less than 1 in 300. Most problems were due to manufacturing defects or labeling errors-not absorption differences.

Even in sensitive areas like epilepsy, where patients and doctors worry about generic switches, a 2022 survey of 412 neurologists showed only 4% believed bioequivalence standards were to blame for any issues. Most problems came from patient adherence, formulation changes, or psychological concerns-not actual pharmacokinetic differences.

The rule’s strength is its consistency. Because every country uses the same standard, a generic made in India can be approved in the U.S., Europe, or Brazil without retesting. That’s why generics now make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. but only 23% of drug spending. Billions are saved every year.

Common Misconceptions and Myths

Many people-including pharmacists and patients-think the 80-125% rule means generics can be 20% weaker or 25% stronger. That’s wrong. The rule doesn’t control the amount of active ingredient in the tablet. It controls how much of that ingredient gets into your bloodstream.

A 2022 survey by the American Pharmacists Association found that 63% of community pharmacists believed the rule meant generics could contain 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s a dangerous misunderstanding. The active ingredient in generics is tightly controlled to be within 95% to 105% of the label claim-just like brand drugs.

Another myth is that the rule is outdated. But recent studies, including a 2022 meta-analysis of 214 bioequivalence studies, confirmed that drugs meeting the 80-125% rule show no clinically meaningful differences in outcomes across 37 drug classes. The rule isn’t perfect, but it’s proven.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

The future of bioequivalence is moving beyond blood levels. The FDA is investing $15 million into model-informed approaches-using computer simulations based on patient genetics, age, and metabolism to predict how a drug will behave. This could one day reduce the need for human studies for certain drugs.

For complex products like inhalers or injectables, regulators are exploring in vitro tests that mimic how the drug is released in the body. If a generic dissolves the same way as the brand in a lab test, maybe it doesn’t need 36 healthy volunteers to take it.

And with advances in pharmacogenomics, we may one day see personalized bioequivalence standards. A drug that works fine for most people might need tighter limits for those with slow metabolizer genes. That’s still years away-but it’s on the horizon.

For now, the 80-125% rule remains the backbone of generic drug approval. It’s not flashy. It’s not perfect. But it’s simple, consistent, and has kept millions of patients safe and treated affordably for over 40 years.

Does the 80-125% rule mean generic drugs have less active ingredient?

No. The 80-125% rule applies to how much of the drug enters your bloodstream (pharmacokinetics), not the amount of active ingredient in the tablet. Generic drugs must contain 95% to 105% of the labeled amount-the same as brand-name drugs. The rule ensures your body absorbs the drug at a similar rate and extent, not that the pill contains less medicine.

Why is a 90% confidence interval used instead of a 95% one?

A 90% confidence interval allows for a 5% error margin on each end, totaling a 10% risk of incorrectly declaring bioequivalence. This is a regulatory compromise: it’s strict enough to catch meaningful differences but flexible enough to avoid rejecting good products due to small, clinically irrelevant variations. Using a 95% CI would make the standard too strict for practical use in drug approval.

Are all generic drugs tested using the 80-125% rule?

Most are-but not all. The rule applies to standard oral immediate-release drugs. For high-variability drugs (like warfarin), scaled bioequivalence allows wider ranges. For complex products like inhalers or topical creams, regulators use alternative methods such as in vitro dissolution testing. Some very simple drugs may even qualify for a waiver if they meet strict dissolution criteria.

Can a generic drug fail the 80-125% rule and still be safe?

If a generic fails the 80-125% rule, regulators won’t approve it. That’s because the rule is designed to catch differences that could affect safety or effectiveness. While some studies show minor variations don’t always lead to clinical problems, the regulatory system errs on the side of caution. Approval requires meeting the standard-no exceptions.

Why do some patients say generics don’t work as well?

Most often, it’s not bioequivalence-it’s perception or formulation differences. Some generics use different fillers or coatings that change how the pill tastes, looks, or dissolves. Patients may notice a difference in side effects or timing, but these are rarely due to absorption levels. Psychological factors also play a role: if you believe generics are inferior, you’re more likely to feel they’re less effective. Post-marketing data shows very few safety issues are linked to true bioequivalence failures.

Chris Garcia

December 28, 2025 AT 07:24The 80-125% rule is one of those quiet miracles of regulatory science-elegant, pragmatic, and deeply human. It doesn’t demand perfection; it demands consistency. In a world obsessed with binary outcomes-safe or dangerous, effective or not-it embraces nuance. The log-transformed confidence interval? That’s not math for math’s sake. It’s math that respects how biology actually works: exponential, asymmetric, and beautifully imperfect. And yet, it’s the backbone of global access to medicine. A Nigerian grandmother gets her hypertension pill because a statistician in Bethesda decided that 80% and 125% were the right boundaries. That’s not bureaucracy. That’s wisdom.

Janice Holmes

December 29, 2025 AT 05:47LET ME TELL YOU ABOUT THE PHARMA INDUSTRY’S LIE. THEY WANT YOU TO THINK THIS IS ABOUT SCIENCE-but it’s about PROFITS. The 80-125% rule? A smokescreen. They’ve known for decades that some generics have different release profiles-especially in extended-release formulations-and yet they still approve them! And then they charge $500 for the brand and $3 for the generic-WHILE TELLING YOU THEY’RE THE SAME. I’ve seen patients have seizures after switching. They don’t report it because the FDA says ‘it’s bioequivalent.’ That’s not science-it’s corporate capture.

Alex Lopez

December 30, 2025 AT 03:12Wow. Olivia, your comment is like a tinfoil hat made of Excel sheets. 😅 The FDA doesn’t approve drugs based on ‘corporate capture’-they approve them based on 30 years of peer-reviewed bioequivalence data. And yes, there are rare cases where patients report issues-but those are almost always adherence, psychology, or fillers, not pharmacokinetics. The 0.34% recall rate? That’s better than your phone’s software updates. Maybe stop yelling into the void and read the 2022 meta-analysis?

Will Neitzer

December 30, 2025 AT 07:26The elegance of the 80-125% rule lies not in its origin, but in its validation. It was not decreed by fiat, but refined through decades of clinical observation, statistical rigor, and international consensus. The use of geometric means and log-transformation reflects a profound understanding of pharmacokinetic variability-not a mathematical convenience. Furthermore, the 90% confidence interval is not arbitrary; it is the result of a deliberate regulatory calculus that balances Type I and Type II error in a context where clinical harm is nonlinear and patient populations are heterogeneous. To dismiss it as ‘arbitrary’ is to misunderstand the very foundation of evidence-based medicine.

Nikki Thames

December 31, 2025 AT 07:04How dare you speak of ‘elegance’ when patients are suffering? You sound like a regulatory lobbyist with a PhD. The fact that 63% of pharmacists misunderstand the rule proves the system is broken. And you want to keep it? You’re not protecting patients-you’re protecting a system that treats human biology like a spreadsheet. The FDA’s ‘0.34%’ statistic? That’s the tip of the iceberg. Most adverse events are never reported. And you call that ‘evidence-based’? I’ve seen patients on levothyroxine who lost their jobs because their generic ‘wasn’t working’-and the system told them it was all in their head.

Gerald Tardif

January 1, 2026 AT 04:15Hey Nikki-I hear you. I’ve been there too. My sister switched generics for her thyroid med and felt like a different person for weeks. It’s terrifying. But here’s the thing: the science says it’s not the absorption-it’s the pill’s color, size, or even the name on the bottle. People panic when the pill looks different. That’s real. And we need to do better-by educating patients, standardizing pill appearance, and listening when they say something’s off. The rule isn’t perfect, but it’s the best tool we have. Let’s fix the communication, not throw out the system.

James Bowers

January 2, 2026 AT 01:23There is no evidence. There is only regulation. The 80-125% rule is not grounded in clinical outcomes-it is a regulatory artifact designed to reduce testing costs. The fact that it has not been disproven does not make it valid. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. And yet, we allow millions of patients to be exposed to this statistical fiction. This is not science. It is administrative convenience masquerading as medical authority.

Olivia Goolsby

January 2, 2026 AT 15:43