When you’re receiving chemotherapy at home, the biggest worry isn’t just the treatment itself-it’s what happens to the drugs after you use them. Chemotherapy medications don’t just disappear after you swallow a pill or finish an IV. They remain active in your body and in the waste you produce for days. If you toss them in the trash like a cold pill or flush them down the toilet, you’re putting your family, your neighbors, and the environment at risk.

Why Chemotherapy Waste Is Different

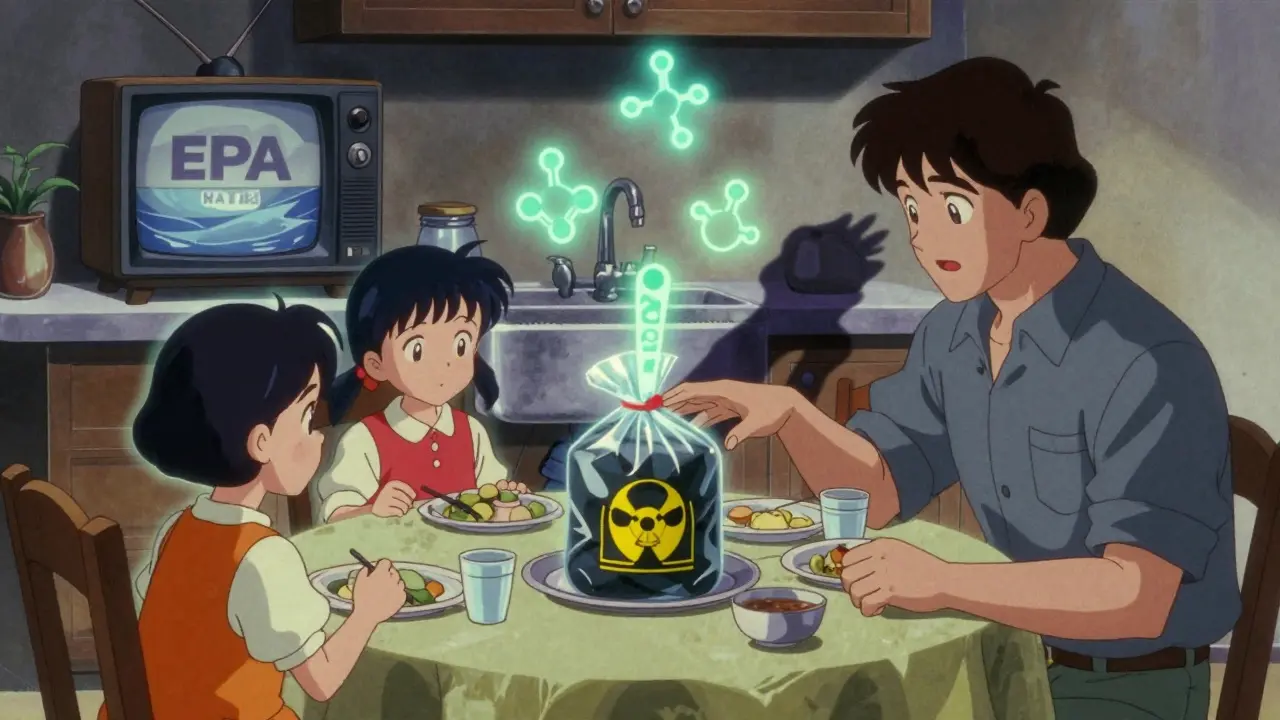

Most medications can be safely thrown away with regular trash. You mix them with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal them in a bag, and call it done. But chemotherapy drugs? They’re not like that. These are cytotoxic agents-designed to kill fast-growing cells. That’s why they fight cancer. But they don’t know the difference between a tumor and your child’s skin, your partner’s lungs, or the water supply. The American Cancer Society says active chemotherapy compounds can stay in your urine, feces, vomit, or sweat for up to 72 hours after treatment. Some studies show traces can linger for as long as seven days. That means if you don’t handle your waste properly, someone touching a toilet seat, cleaning up a spill, or emptying your trash could be exposed to dangerous chemicals. The Environmental Protection Agency found detectable levels of cyclophosphamide-a common chemo drug-in 67% of U.S. waterways. That’s not from hospitals. That’s from homes. Flushing chemo meds, even if they’re on the FDA’s flush list for other drugs, is strictly forbidden for chemotherapy agents.What You Need to Handle Chemotherapy Waste

You won’t be doing this with bare hands or a regular plastic bag. Proper disposal requires specific tools and steps:- Nitrile gloves (minimum 0.07mm thick)-not latex. They resist chemical penetration.

- Two leak-proof plastic bags-each at least 1.5 mil thick. The inner bag holds the waste; the outer bag seals it in.

- Yellow hazardous waste containers-often provided by your oncology team. These are for solid waste like used syringes, empty vials, and gloves.

- Dedicated cleaning supplies-paper towels, wipes, and spray bottles that are never reused for household cleaning.

- Zip-ties or heat-sealing tools-to seal the inner bag before putting it in the outer one.

How to Dispose of Different Types of Chemotherapy Medications

The method changes depending on how you take the drug:Oral Pills and Capsules

Never crush, chew, or split pills. That releases dust that can be inhaled or absorbed through skin. Wear gloves when handling them, even if you’re just counting them out. After taking the dose:- Place empty pill bottles, blister packs, or any leftover pills into the inner leak-proof bag.

- Seal it tightly with a zip-tie.

- Put that bag into a second identical bag and seal it again.

- Label it clearly: “Hazardous Chemotherapy Waste-Do Not Open.”

Transdermal Patches

These stick to your skin and release drugs slowly. But even after you peel them off, they’re still active.- Immediately fold the patch so the sticky sides stick together.

- Place it in the inner bag, then the outer bag.

- Wash your hands thoroughly after handling.

Liquid Medications and IV Bags

If you’re using liquid chemo at home:- Always wear gloves when preparing or cleaning up.

- Never pour leftover liquid down the sink or toilet.

- Use an absorbent material like kitty litter or paper towels to soak up spills or unused liquid.

- Place the soaked material in the inner bag, seal it, then place it in the outer bag.

Used Syringes, IV Lines, and Needles

These go into a sharps container-but not just any one. Use the red, puncture-proof container your provider gave you. If you don’t have one, ask for it. Never reuse containers. Once full, seal it and put it in the yellow hazardous waste bin.What to Do After Treatment

The danger doesn’t end when you finish your last dose. For 48 to 72 hours after treatment, your body is still releasing active drugs.- Flush the toilet twice after each use.

- Wash your hands thoroughly after using the bathroom.

- Wear gloves when cleaning up vomit, urine, or stool.

- Use disposable wipes or paper towels-don’t reuse cloths.

- Keep towels, bedding, and clothes used during this time separate from the rest of the laundry. Wash them alone in hot water.

What NOT to Do

There are a lot of myths out there. Don’t fall for them:- Don’t flush. Even if the bottle says “flush if no take-back,” that doesn’t apply to chemo. The FDA explicitly says no chemotherapy drugs should ever be flushed.

- Don’t use Deterra or similar deactivation systems. These work for painkillers and antidepressants-but not for cytotoxic drugs. The Deterra website clearly states they’re not approved for chemotherapy.

- Don’t throw it in the regular trash without double-bagging. Trash collectors, recycling workers, and even your kids could be exposed.

- Don’t give leftover pills to someone else. Even if they have cancer, your prescription is not theirs. This is illegal and dangerous.

What About Take-Back Programs?

You’ve probably seen those MedDrop kiosks at pharmacies. They’re great-for regular meds. But only 63% of chemotherapy drugs are accepted. That’s because many chemo agents are too hazardous for standard collection systems. Only 34% of U.S. pharmacies accept chemotherapy waste at all. And mail-back programs? Just 28% of pharmacies offer them for chemo. Community take-back events are even rarer-only 12% accept chemo waste because of the special handling required. So while it’s worth checking if your local pharmacy takes it, don’t rely on it. Most of the time, you’ll need to dispose of it at home.What If You Have a Spill?

Spills happen. You drop a pill. A vial breaks. Liquid leaks. The Cancer Institute of New Jersey outlines a 15-step cleanup process. Here’s the simplified version:- Put on gloves, a gown, face shield, and mask.

- Use disposable paper towels or wipes to soak up the spill.

- Place all cleanup materials into the inner leak-proof bag.

- Wash the area with warm water and detergent.

- Wipe the surface again with fresh towels.

- Seal the bag and put it in the outer bag.

- Label it clearly.

- Wash your hands thoroughly.

Why So Many People Get It Wrong

A 2022 survey by CancerCare found that 68% of patients needed multiple training sessions just to learn how to dispose of their meds safely. That’s not because they’re careless-it’s because the instructions are confusing, inconsistent, or poorly explained. Memorial Sloan Kettering scored 9.2 out of 10 for clear disposal instructions. The industry average? 6.8. That gap matters. In Stericycle’s 2022 report, 41% of patients improperly disposed of chemotherapy drugs-compared to 29% for regular medications. The problem isn’t just knowledge. It’s access. If your provider doesn’t give you the right bags, gloves, or training, you’re left guessing. Ask for materials. Ask for a written guide. Ask for a video walkthrough.What’s Changing

Good news: things are improving. In March 2023, the FDA required all oral chemotherapy drugs to include clear disposal instructions on their labels. That affects 147 medications worth over $8 billion annually. The EPA has allocated $4.7 million to research better disposal methods through 2026. New systems like ChemiSafe and the Oncology Waste Management Unit are in testing and could be available soon. The American Cancer Society and Stericycle have placed over 1,800 MedDrop kiosks that now accept certain chemo drugs across 47 states. More are coming. But until those systems are everywhere, the responsibility is still on you.Final Reminder

You’re not just protecting yourself. You’re protecting your partner, your kids, your pets, the sanitation workers who empty your bin, and the rivers your grandchildren will swim in. Double-bag. Wear gloves. Don’t flush. Don’t guess. It’s not complicated. But it’s critical.Can I flush chemotherapy pills down the toilet?

No. Never flush chemotherapy pills or liquids. Even if the FDA allows flushing for some medications like opioids, chemotherapy drugs are explicitly excluded. Flushing them contaminates water supplies and can harm aquatic life. The EPA and American Cancer Society both state that flushing chemotherapy waste is dangerous and prohibited.

What should I do with leftover chemo pills?

Never give them to someone else or keep them for later use. Place unused pills, empty blister packs, or broken capsules into a leak-proof inner bag, seal it, then place it into a second identical bag. Label it clearly as hazardous waste. If your oncology team provides a disposal container, use that instead. Contact your provider if you’re unsure how to proceed.

Can I use Deterra or similar drug deactivation systems for chemo?

No. Deterra and similar systems use activated carbon to deactivate medications-but they are not approved for cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs. The Deterra website explicitly states their system is not suitable for hazardous chemotherapy agents. Using it could leave active toxins in the waste, creating a false sense of safety.

How long should I keep using precautions after my last chemo dose?

You should continue taking precautions for 48 to 72 hours after your last treatment. Active chemotherapy compounds can remain in your urine, feces, sweat, and vomit for up to three days. During this time, flush the toilet twice after use, wear gloves when cleaning spills, and wash your hands thoroughly after using the bathroom. Avoid sharing towels or linens until after this period.

Where can I get disposal supplies like gloves and bags?

Your oncology clinic or hospital should provide you with disposal supplies when you start home chemotherapy. This includes nitrile gloves, leak-proof bags, and hazardous waste containers. If you run out, ask your nurse for replacements. Some pharmacies or home health agencies may also supply them. Do not substitute with grocery bags or regular plastic containers-they are not strong enough to prevent leaks.

Is it safe to wash chemo-contaminated clothes with the rest of the laundry?

No. Any clothing, bedding, or towels that have come into contact with chemotherapy drugs (including sweat or bodily fluids) should be washed separately in hot water. Use gloves when handling soiled items, and wash them alone to avoid contaminating other laundry. Avoid using the same washing machine for regular clothes immediately after-rinse the drum thoroughly after washing contaminated items.

Are there any legal consequences for improper disposal?

While individuals are rarely prosecuted for home disposal mistakes, improper handling of chemotherapy waste violates EPA regulations under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. Healthcare providers and pharmacies can face fines for improper handling, and some states have specific laws requiring safe disposal. More importantly, improper disposal puts public health at risk, which is why education and proper procedures are emphasized over punishment.

Can I take unused chemo meds to my local pharmacy?

Some pharmacies participate in take-back programs, but only 34% accept chemotherapy waste. Even then, only 63% of chemo drugs are eligible. Before going, call ahead and ask if they accept hazardous oncology waste. If not, follow your provider’s home disposal instructions. Don’t assume your local pharmacy can handle it-most can’t.